Ross Winn: Digging Up a Tennessee Anarchist

In the early 2000s, I met the anarchist historian Robert Helms at a bowling alley in Ohio during an activist media conference, and he told me about an obscure, long-dead anarchist publisher from my then-home in central Tennessee, Ross Winn. I didn’t know it at the time, but the beginnings of my obsession with finding obscured histories was born that weekend.

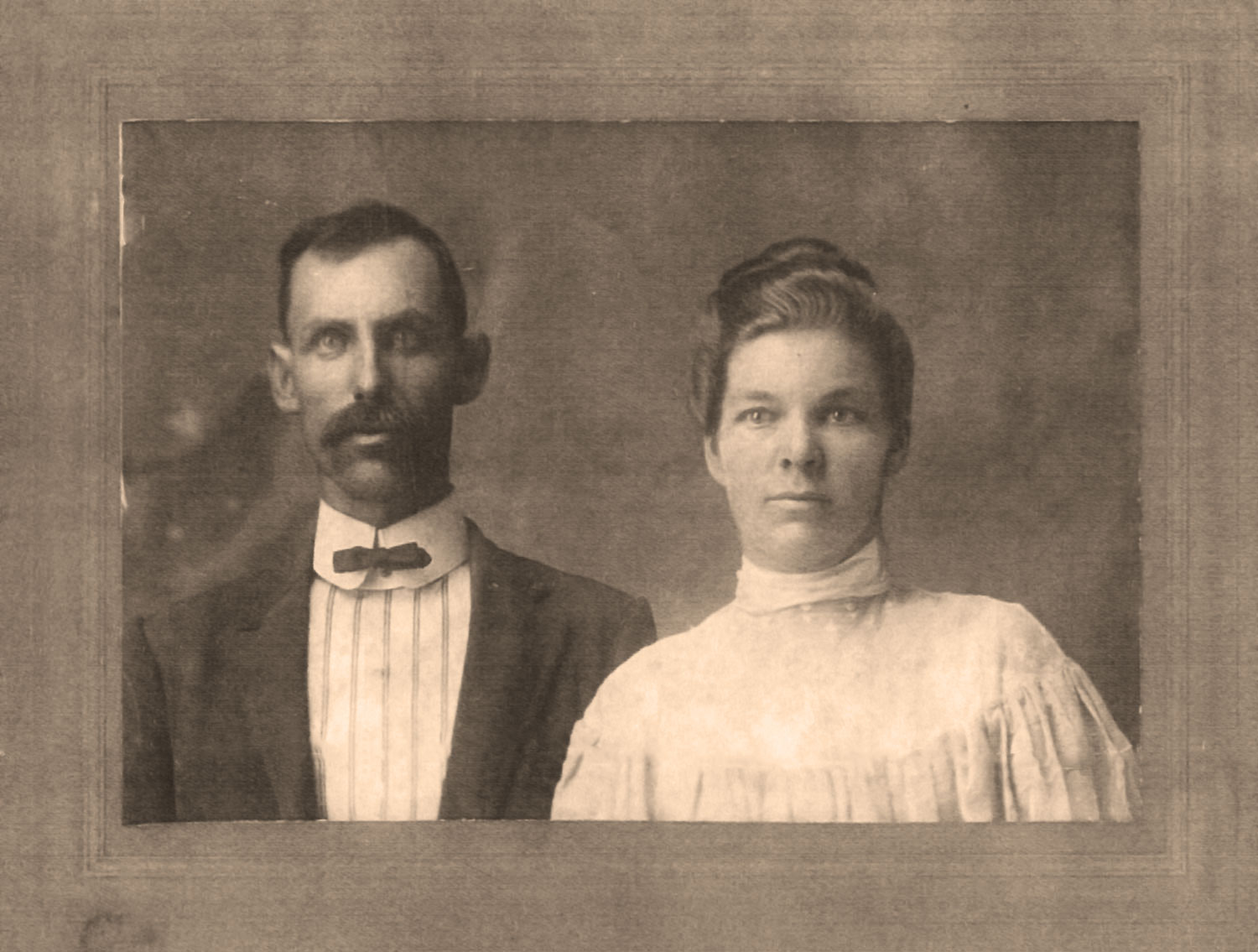

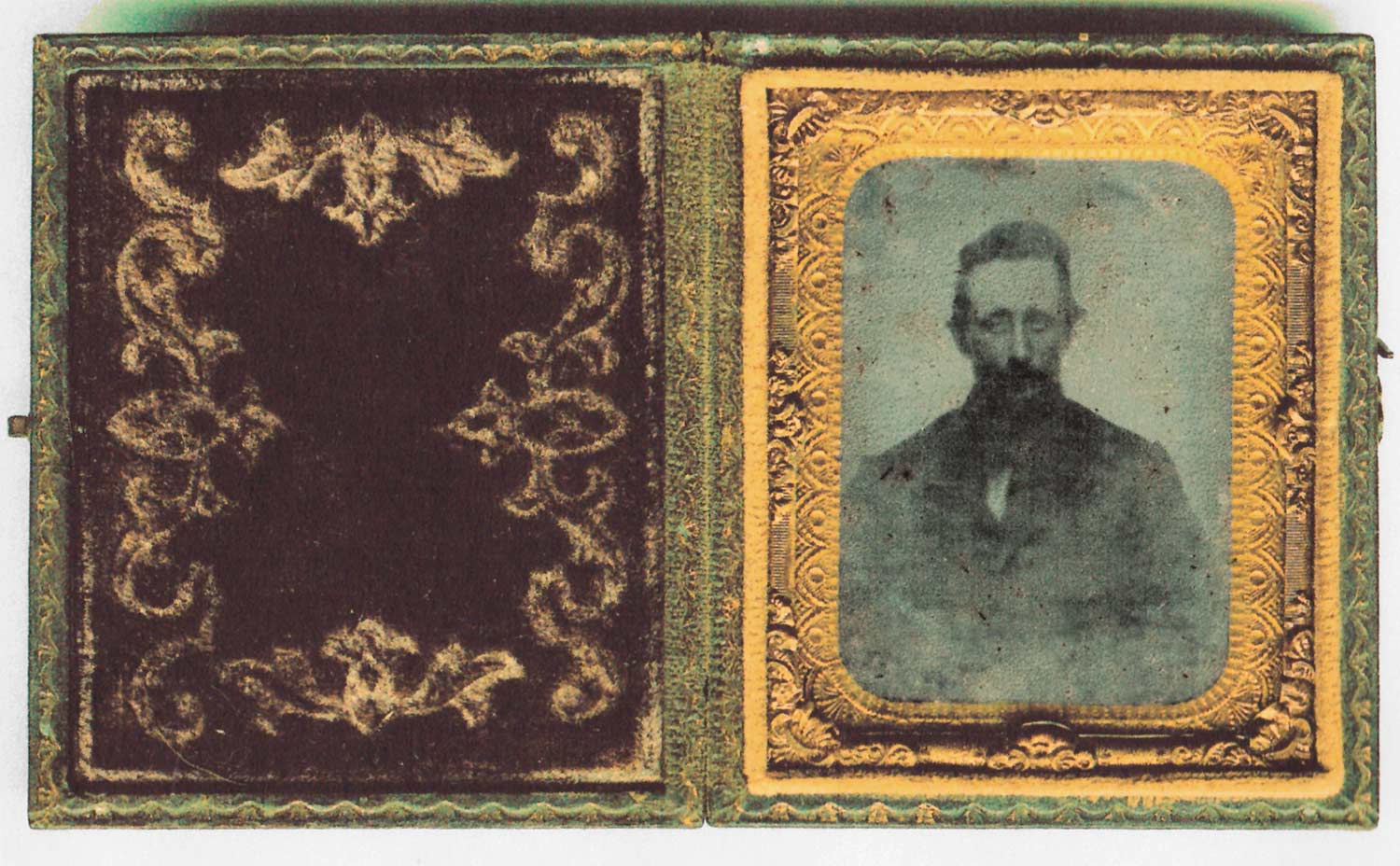

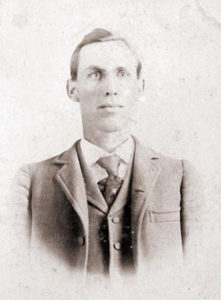

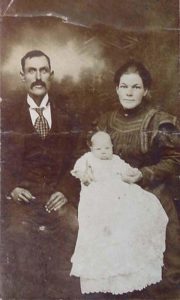

Bob inspired my cohort Ally Reeves and I to find Ross Winn’s grave, and a couple of years later we found it. That journey led us to the old house that he and his wife had lived in at Mt. Juliet, Tennessee, and Ally and I were eventually able to find living relatives and never-before-seen portraits and newspapers. Years after learning his name, we could sketch out Ross’ life story. Prior to this work, only a couple of details about Ross’ life were publicly known, and no photographs were available. Now, all of the available information on the internet stems from our original research, with particular help from our friend Ryan Kaldari and special attention from Julie Herrada at the Labadie Collection.

In 2006 we self-published a large edition of a zine detailing Ross’ life and our path in finding it, Ross Winn: Digging Up a Tennessee Anarchist. While that 44-page, illustrated zine is now out of print, you can see (and download) a scanned copy of it at the Internet Archive, and read the introduction that Bob Helms wrote for the publication. Ryan Kaldari has uploaded and transcribed all of the writing we have by Ross to WikiSource here. A combination of our own research and the generosity of the Labadie Collection (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) culminated in scans of many of Ross’s articles and all archived copies of both Winn’s Firebrand and The Advance, his last published paper, available at WikiMedia Commons.

Ross Winn: Biographical Sketch

- The first version of this article was printed in Fifth Estate, Spring 2004.

- The second, updated printing appeared in the self-published zine

Ross Winn: Digging Up a Tennessee Anarchist, winter 2005. - The current text below is based on updated information as of March, 2006

and has not been updated since that time.

. . .

From the woods of rural Tennessee, in the early part of the last century, a man named Ross Winn toiled under the burdens of continual poverty, conservative Christian surroundings, and the later, terminal grip of tuberculosis to dedicate his life to the printing of revolutionary anarchist literature. If the setting sounds overly romantic, so did a lot of the man’s printed prose. Ross was a poet at heart, and his drive to provide the American anarchist movement with an “organ of radical thought” never got in the way of his lyrical embellishments and genuine skill at ripping into his targets with the printed page.

Ross Winn was born in Dallas, Texas on August 25, 1871. He was descended from German immigrants, but little is known about his early years. Ross picked us typesetting as a trade very early in his life, a skill that he would continue with as he published and contributed to various anarchist publications in the coming years. He clearly understood the value of the free press at an early age, and sought to learn it’s inner workings for himself. Using this knowledge, he could provide literature and propaganda that reflected the society he and so many others were working towards. In the late 1800’s, every publishing endeavor was “DIY”, and radical endeavors could expect the same scarce funding and lack of assistance that they experience today. A hundred years ago, putting out a paper required a proficiency in typesetting, a time-consuming process by which each letter on each page was laid out by hand and the pages then printed individually. Ross worked as a field hand (he was the son of farmers) picking cotton until he made enough money to purchase his first printing outfit. It isn’t clear where his formal education ended, exactly, but he never formally attended a University.

Ross Winn was born in Dallas, Texas on August 25, 1871. He was descended from German immigrants, but little is known about his early years. Ross picked us typesetting as a trade very early in his life, a skill that he would continue with as he published and contributed to various anarchist publications in the coming years. He clearly understood the value of the free press at an early age, and sought to learn it’s inner workings for himself. Using this knowledge, he could provide literature and propaganda that reflected the society he and so many others were working towards. In the late 1800’s, every publishing endeavor was “DIY”, and radical endeavors could expect the same scarce funding and lack of assistance that they experience today. A hundred years ago, putting out a paper required a proficiency in typesetting, a time-consuming process by which each letter on each page was laid out by hand and the pages then printed individually. Ross worked as a field hand (he was the son of farmers) picking cotton until he made enough money to purchase his first printing outfit. It isn’t clear where his formal education ended, exactly, but he never formally attended a University.

The earliest published writing we have found so far by Ross is from the magazine Twentieth Century, in January of 1894. He was 23 years old when he wrote the piece, a plea for unification within the anti-capitalist movement. Entitled “Let Us Unite”, it makes clear that even as a young man Ross saw that too much division between the different social movements of his time would continue to hold all of them back, and would work instead in the favor of the totalitarian governments they sought to dissolve. Putting differences aside, he proclaims “we have had coercion enough. For ages man has ruled with sword and bayonet, with bars and chains… and now are we not civilized enough to dispense with it forever?”. In a later piece, appearing in the paper Free Society in December of 1900, makes mention of him becoming a “young ‘convert’ ” and finding an outlet for his own radical views some twelve years earlier, when he was only 17 years old. Ross, like many other young radical thinkers and organizers of his day, was no doubt aroused by the atrocities which amounted to the “Haymarket Affair” in May of 1886. There, eight anarchist organizers in Chicago were convicted of conspiracies against the government, after police raided a meeting which was called to address the escalation of police violence at a worker’s rights rally three days earlier. A bomb went off during the raid, injuring several on both sides and instigating massive arrests and beatings from local law enforcement. The event is widely regarded as having helped spur a more fervent national movement after a skewed trial resulted in prison for three and execution for four of the eight men who were eventually tried.

Putting differences aside, he proclaims “we have had coercion enough. For ages man has ruled with sword and bayonet, with bars and chains… and now are we not civilized enough to dispense with it forever?”. In a later piece, appearing in the paper Free Society in December of 1900, makes mention of him becoming a “young ‘convert’ ” and finding an outlet for his own radical views some twelve years earlier, when he was only 17 years old. Ross, like many other young radical thinkers and organizers of his day, was no doubt aroused by the atrocities which amounted to the “Haymarket Affair” in May of 1886. There, eight anarchist organizers in Chicago were convicted of conspiracies against the government, after police raided a meeting which was called to address the escalation of police violence at a worker’s rights rally three days earlier. A bomb went off during the raid, injuring several on both sides and instigating massive arrests and beatings from local law enforcement. The event is widely regarded as having helped spur a more fervent national movement after a skewed trial resulted in prison for three and execution for four of the eight men who were eventually tried.

Ross continued to write and contribute to other radical papers, most notably Free Society, the eventual incarnation in Chicago of the weekly anarchist paper The Firebrand, which had seen a brief but renowned life out of Sellwood near Portland, Oregon from 1895-97. The Firebrand, like many other papers at the time, received continual harassment from police and postal authorities, often on grounds of obscenity and conspiracy. Sometime in 1894, Ross began his first paper, known as Co-operative Commonwealth. He then edited and published Coming Era for a brief time in 1898 and Winn’s Freelance in 1899. There isn’t much left over from these early forays into the realm of self-publishing. Unfortunately, as soon as November of 1899, the intrepid young publisher succumbed to the troubles of a complication that would continue to burden him for the rest of his life: how to offer and consistently maintain an interesting and good quality paper, each page hand printed, for an affordable subscription rate without sliding quickly into debt. Ross was forced to cease publication, and called on his readers to turn their support, financial and otherwise, towards Free Society.

He was by no means discouraged, however, and in 1902 he was at it again. In a June issue of Free Society he made the announcement of the upcoming publication of his new paper: Winn’s Firebrand, the name aptly describing the devotion and zeal that Ross put into his new endeavor. His vision was for a paper that would “occupy an entirely new field. It will appeal to the cultured, the thoughtful, the progressive of all classes. It will be just the kind of literature for missionary work among the masses.” Clearly, Ross saw the printed magazine as a vital tool for social change, and viewed he distribution of anti-authoritarian ideals through the free press as a distinct calling, a work he viewed as a passionate personal duty. Tennessee became his new home base for this endeavor: “In establishing the magazine (in Mt. Juliet, TN) as an independent publication, the flag of revolutionary thought is planted on Southern soil, and a residence of a lifetime in this section convinces me that it will be a fruitful field for libertarian ideals, if the right methods are used to present them.” (The term “libertarian”, incidentally, was originally synonymous with anarchism, adopted mainly to elude the derogatory treatment of the word “anarchy” in the mainstream media of the day.)

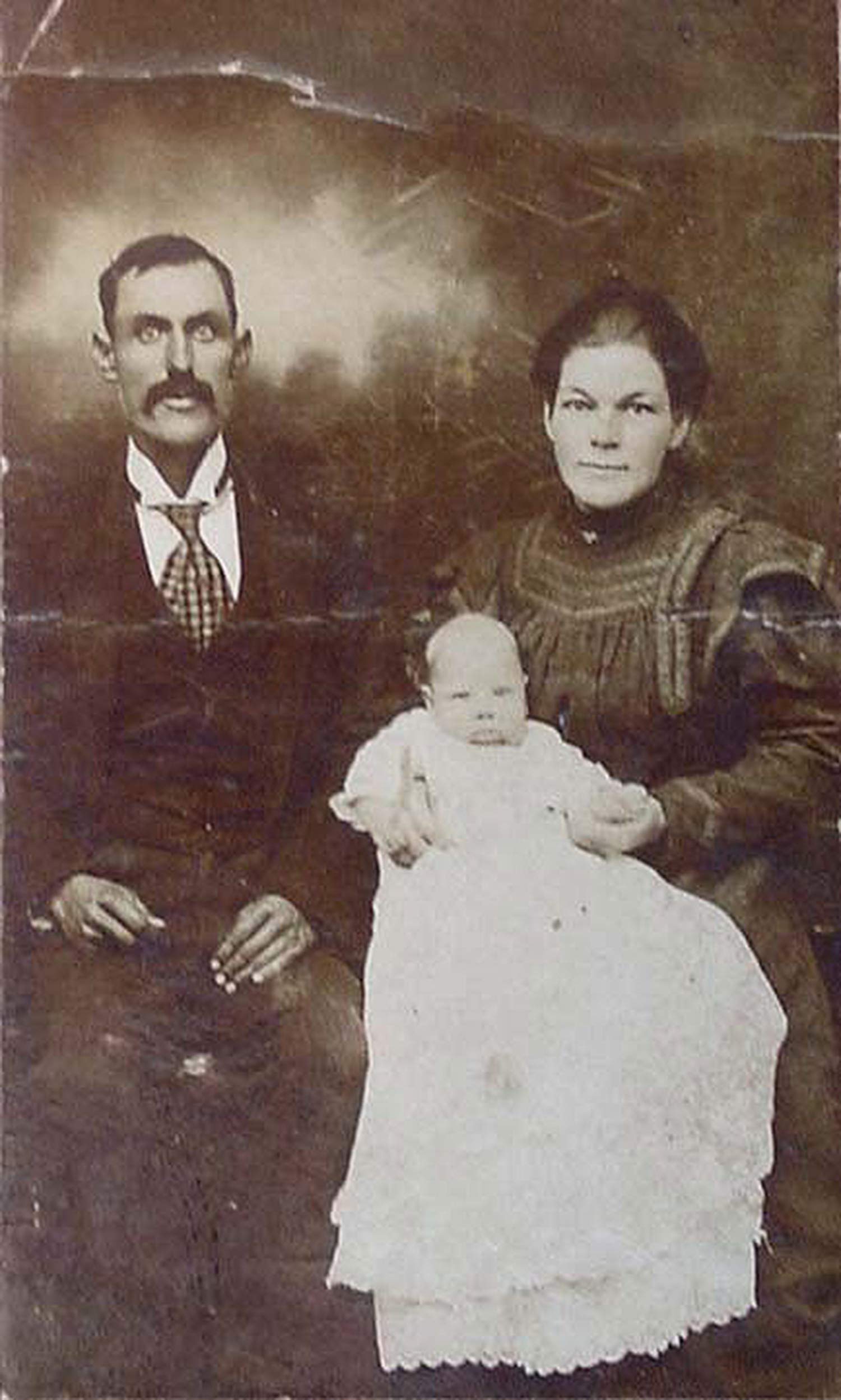

In August of 1900, Ross’ partner, Augusta Gertrude Smith (known affectionately as “Gussie”) gave birth to their first and only son: Ross Jr. His birthday was only five days before his father’s. Ross and Gussie had married just a year earlier, and he found in her a strong and willing friend. The two stuck together throughout his life, often in abject poverty. They moved into her family’s home in Mt. Juliet, Tennessee, an old house originally built in the 1790’s and later purchased by Gussie’s father, who ran a general store and a mill nearby. The area where the house stands is also known as “Silver Springs”, named for a tiny branch of the nearby Cedar Creek that the home was built along.

In the same year, Ross met Emma Goldman in Chicago, and the two became allies. As she would later write, Emma “was deeply impressed with his fervor and complete abandonment to the cause, so unlike most American revolutionists, who love their ease and comfort too well to risk them for their ideals.” (Mother Earth, September, 1912) Ross kept up a correspondence with her throughout his life, as he did with several other prominent anarchist writers and thinkers of the time. Joseph Labadie, a publisher and organizer in Detroit, Michigan, was another friend to Ross, and saw to regular contributions to Winn’s Firebrand in it’s later years.

Within his papers, Ross devoted his own columns to criticisms of everyone from Theodore Roosevelt to local preachers and independent publishers. He railed against the Socialist party, which to he and other anarchists seemed to claim merely hollow victories for political reform even as their national influence continued to grow. He responded (usually with venom) to the reporting of the regional mainstream newspapers: the Memphis Commercial-Appeal, the Nashville Banner, Nashville Democrat, and Nashville American to name a few. He also offered his bold opinions on the coming alcohol prohibition, the American electoral politics game, labor strikes around the world, and, as often as possible at the risk of redundancy, the organized Church. Ross, like many anarchists in his day, believed that the teachings attributed to Jesus Christ were in many ways the same as their own moral principles, but that the Church (in conjunction with the State), had twisted and distorted them into measures of control. “I suppose some people will object if i call Jesus an Anarchist,” he writes in a December, 1902 issue of Winn’s Firebrand, “but I am sure the whole world would call him that if he lived to-day, and preached such doctrines.”

Within his papers, Ross devoted his own columns to criticisms of everyone from Theodore Roosevelt to local preachers and independent publishers. He railed against the Socialist party, which to he and other anarchists seemed to claim merely hollow victories for political reform even as their national influence continued to grow. He responded (usually with venom) to the reporting of the regional mainstream newspapers: the Memphis Commercial-Appeal, the Nashville Banner, Nashville Democrat, and Nashville American to name a few. He also offered his bold opinions on the coming alcohol prohibition, the American electoral politics game, labor strikes around the world, and, as often as possible at the risk of redundancy, the organized Church. Ross, like many anarchists in his day, believed that the teachings attributed to Jesus Christ were in many ways the same as their own moral principles, but that the Church (in conjunction with the State), had twisted and distorted them into measures of control. “I suppose some people will object if i call Jesus an Anarchist,” he writes in a December, 1902 issue of Winn’s Firebrand, “but I am sure the whole world would call him that if he lived to-day, and preached such doctrines.”

Similar to the anti-copyright ethics of a lot of today’s alternative and anarchist magazines, Ross also pulled classic pieces from well-known writers. Authors like Peter Kropotkin, Elisee Reclus, Robert Ingersol, Lucy and Albert Parsons, Voltaire and Tolstoy filled columns alongside his own writing and poetry and published letters from readers across the country. Also included were reviews of books and pamphlets that would have been of interest to his readers. Some, such as Lucy Parsons’ text on the “Haymarket Martyrs” or Tolstoy’s “The Slavery of Our Times” could be ordered through the paper. Works of fiction were also common – Ross was concerned, after all, with creating more than just a political newspaper.

For a short period in 1905, Ross took up residency in Nashville on Jefferson Street in the Northern part of the city near Fisk University. There, he briefly published a paper titled To-Day: A Journal of Politics. This paper put forth a much more moderate approach to the issues of the times, and curiously does not assert itself as an anarchist publication at all. Instead, Ross more vaguely proclaims To-Day “a journal of radical truth and advance thought”. The content mirrors that of his other papers, but diverts in some cases to a sudden and vocal support for the Socialist movement; yet Ross proclaimed that “in changing the name from Winn’s Firebrand to To-Day, we have in no wise changed it’s policy and purpose”.

To-Day may have only lasted one issue, though, and Ross found himself back in Mount Juliet soon enough, occupying an upstairs room of the Smith house with Gussie and Ross Jr. He continued to work on printing issues of Winn’s Firebrand with as much regularity as his finances would allow, using a small hand-operated press which was kept in their bedroom to print each page. Gussie’s family doesn’t seem to have had much tolerance for Ross or his ideals, and whether this was simply a result of a conservative Southern Christian climate or Ross’ personality, we can’t really know. One story that was related to us involved a “meeting” Ross was supposed to have attended out of town. This was in 1901, in the months before Leon Czolgosz shot and killed then-president William McKinley. Czolgosz claimed to have received his inspiration from Emma Goldman and the anarchist movement. Even though it was widely thought that he was merely seeking an ideological justification for actions he intended to commit anyway, it became a dangerous time to speak of anarchism. As the story went, Ross was very agitated in the days before he left for this meeting, and very relieved when he returned. The rumor, since passed through the generations, was that he had attended a sort of straw-drawing, where the anarchist who drew the shortest straw was charged with the task of assassinating the president. Ross, then, was obviously relieved to have escaped such a responsibility. It might seem absurd to us now, but stories like this often surround the misunderstood, and illustrate just how little trust Gussie’s family had in her lover and husband.

Probably sometime in 1909, Ross contracted tuberculosis. Known popularly then as “consumption” (because sufferers lost so much weight, as though they were being consumed from the inside), the disease has roots in bovine bacterial infections and was probably originally spread to humans as a byproduct of the domestication of cattle. Typically, only people with compromised immune systems brought upon by malnutrition from poverty are unable to fight the disease off. It can take years for tuberculosis to finally take it’s toll on the body, and although treatments and preventative measures exists today, drug-resistant varieties continue to evolve in the world’s poorest countries.

Ross continued his tireless work on The Firebrand, despite his failing health. In July of 1910, Ross, Gussie, and Ross Jr. moved to Sweden, Texas. That September Ross left his family in Sweden and went to San Antonio for a couple of months to look for work. Within another couple of months he had run out of the funds to keep The Firebrand going. Unable to find work, Ross got himself into debt and eventually had to sell his printing press in order to fund he and his family’s return to Mt. Juliet in May of 1911.

This became an increasingly time for Ross and Gussie, as they had little or no money and Ross’ condition made it more and more difficult for him to earn a living for his family or work on his paper. In a June 1911 issue of The Agitator, Ross announces that the past November’s was the last issue of his paper until further notice. The Agitator, published by Jay Fox out of the anarchist Home Colony in Lake Bay Washington, picked up the remaining subscribers to Ross’ paper. That next month, Gussie wrote a desperate letter, in secret, to Emma Goldman. In it, she asks for any possible financial assistance from Emma or her network of friends, knowing that Ross “would rather starve than beg” for help from anyone. The word was sent around and money was raised quickly: some $60 total and a small fortune for a family in such dire need. Those who respected and encouraged Ross and his work were not about to let he and his family starve.

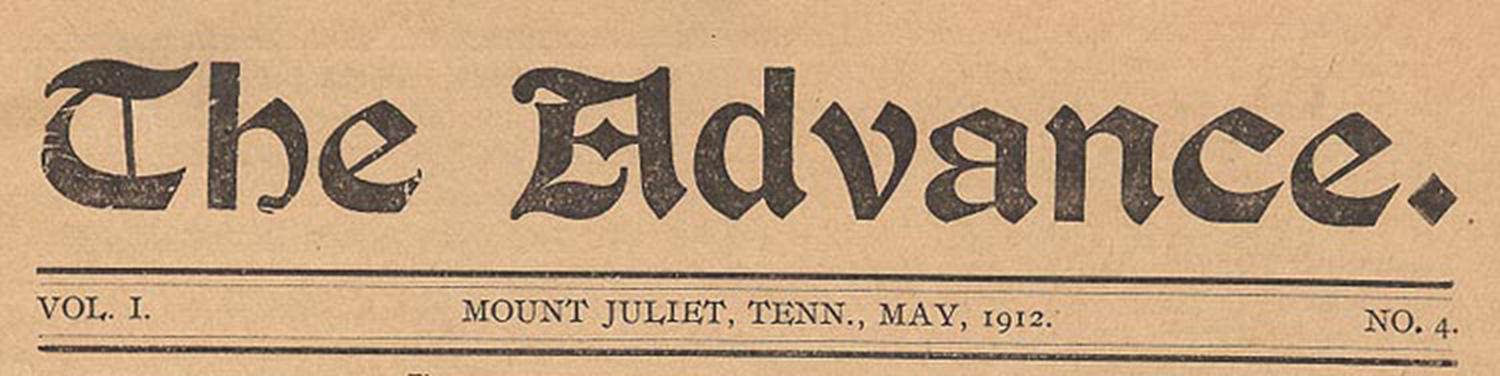

Ross had other plans, though, and refused to spend the money that “the comrades” had sent to him on himself or his wife and son. Instead, seeing it as an opportunity to fund a new endeavor and further the publishing of anarchist literature, he spent the majority of the money on a new printing outfit to replace the one he lost in Texas. The Advance, which was to be his final paper, was born in December of 1911 (much to the surprise of several of his far-flung acquaintances, whose letters in later issues of The Advance express surprise that Ross was still alive and printing). “Sixteen pages of brain-stirring stuff that will tear the moss from your mind” said Fox in the January issue of Agitator. But the sacrifice this meant for his family, and the friendly contributions that ultimately funded it’s printing, went unmentioned in the pages of The Advance.

On August 8, 1912, the degenerative infection of tuberculosis finally took Ross’ life at age 40. He was setting type for the seventh issue of his paper the day before he died. Ross was buried in his Gussie’s family cemetery (Smith-Houser), situated across the highway from where the original house still stands in Mt. Juliet. His gravestone is blank, as are most of the others, but is curiously set apart from the rest of the stones in that it is a simple, rectangular concrete slab. In the room where he died, there is a scar in the original floorboards where a pan of sulphur was burned upon his death: a practice that in Ross’ day was thought to sterilize a room where consumption had taken a life.

Ross’ son kept up a bit of correspondence with his father’s friends throughout his life. In a letter to Emma Goldman in 1934, he tells her that his father burned most of his writings just before his death. If it is true that Gussie’s family knew little of Ross’ work and held mostly fear and contempt for him, than perhaps he felt it best that his work didn’t bring his wife and son any more harm by being discovered by a curious relative. Either that or someone else burned the work themselves, and the deed was passed on as the final, dramatic act of an eccentric and radical poet. To this day we don’t know the truth, we have only assumptions and, of course, questions.

Gussie took Ross Jr. to Chicago for a time soon after the funeral. Although much of the family’s original furniture still exists in the old house, Ross’ printing setup is absent, and was probably sold by Gussie for the money she could use to support her and their son. She eventually moved to Oklahoma and married a Mr. Cross, although she is buried near Ross in the same cemetery back in Tennessee. Gussie lived to be 67 years old. Ross Jr. eventually ended up in St. Louis, Missouri, where he married and had one daughter, Cleo Winn, who passed away only in the last few years.

Emma Goldman’s glowing obituary of Ross, published in Mother Earth and paraphrased in several other papers in the months following his death, is a testament to the influence that this farmer’s son turned radical publisher had on the anarchist movement of the last century – a time when revolutionary anarchist ideology was arguably more influential in the mainstream than at any other time in American history. “Never has the power of the Ideal been demonstrated with greater force than in the life and work of this man,” she wrote, “for nothing short of a great ideal, a burning, impelling, all-absorbing ideal, could make possible the task that our dead comrade so lovingly performed during a quarter of a century… His were dreams of the world, of humanity, of the struggle for liberty.” In this same text, Emma calls again for funds to help Gussie and their son, quietly pointing to Ross’ expenditure of their original contributions and the still immediate need of those who loved him.

Not much of Ross’ work has survived him. Until our research, his name was largely relegated to the obscure memories of a handful of anarchist historians to whom his name was familiar in the background of the history of the independent press. Several of his letters to Joseph Labadie, as well as a handful of issues of Winn’s Firebrand, The Advance, and the sole issue of To-Day exist at the Labadie Collection of Social Protest Literature at the University of Michigan Library in Ann Arbor. Portions of a correspondence between his son and Emma Goldman can be found in the Emma Goldman Papers Collection, as does the secret letter from Gussie detailing their plight. The rest remains scattered about the country, perhaps surviving in the memorabilia of families of Ross’ subscribers or the quiet collections of rare book aficionados. As we continue to discover and pursue these clues and secure the memory of Ross’ work, our hope remains that those who struggle for the same dreams of liberty today can draw inspiration from the courageous work of those who did so in our past.

Date

2004

Category

People's History: Research & Writing